Ward Village: Recreation, Restaurants and Retail

What is there to do in Ward Village? Explore all the options.

Before land ownership in Hawaii, the Hawaiian Islands, or mokupuni, were divided into smaller parts, or moku. From Waikiki to Honolulu, where Ward Village exists, the moku was called Kona.

And, the moku were further divided into ahupua‘a that ran from the mountains to the sea. Each ahupua‘a was divided to ensure it had all the necessary resources to live – from the ocean for fishing to the land for farming and building homes.

Ward Village is in the ahupua‘a of Waikiki. The ahupua‘a of Waikiki was a geographically larger area of land than most ahupua‘a on Oahu – presumably because much of Waikiki was swampland, including much of the current condos in Ward Village, and it did not have as many resources as other nearby ahupua‘a.

This ahupua‘a of Waikiki, roughly translated to “sprouting waters,” was ruled by an ali‘i or local chief with maka‘ainana, or common people, who lived there and worked the land with their specialized trade, such as farming, fishing, weaving, building canoes, taking care of the home or more.

King Kamehameha united the Hawaiian Islands into a single kingdom in 1795, and in the proceeding years under his reign, the swampland within and surrounding Ward Village would be used to make fish ponds, to grow taro and also to produce salt. The shoreline around Ward Village, known as Kewalo, was “a place of fishing, canoe landings, cleansing and religious practices,” according to the Ward Neighborhood Master Plan.

The Office of Hawaiian Affairs also shares extensive cultural context behind the waterfront area in their Kakaako Makai Background Analysis.

With the word spreading about Hawaii worldwide, King Kamehameha III decided it was time for people to own land. Known as the māhele, all the land in Hawaii was divided in 1848. In 1850, the Kuleana Act allowed for the commoners or maka‘āinana to petition for title to the land they lived on (since before 1839) and own it as fee simple property. However, much of the land remained unclaimed after this time, with the majority of land owned by royalty or the government.

Then, the Resident Alien Act of July 10, 1850, gave foreigners or non-Hawaiians the right to buy land in fee simple, meaning individuals from anywhere could buy and sell land or pass it on to heirs – and this led to Ward Village’s next era.

The swamplands comprising the current Ward Village had been largely unchanged despite the urbanization in the nearby current areas of Downtown Honolulu and Waikiki. In the 1870s, “traffic was nonexistent and almost all commerce was relegated to a few blocks near the harbor and Downtown. At the time, Kakaako was a nearly empty stretch of land and most of the city’s residents regarded it as a dusty destination too far removed from the port,” according to a Ward Village article.

Then, from the 1860s to 1880s, a couple named Curtis Perry “C.P.” Ward and Victoria Ward acquired 100 acres through a series of transactions. The land “extended from King Street to the ocean, bound on the Ewa side by the Catholic cemetery and the land that would later house McKinley High School in the Diamond Head Side,” according to a story by Hawaii Public Radio.

Their life was detailed in the book, “Victoria Ward and Her Family,” published in 2000 by Victoria Ward’s great-great grandson Frank Ward Hustace III and summarized in a story published in Pacific Business News in 2019.

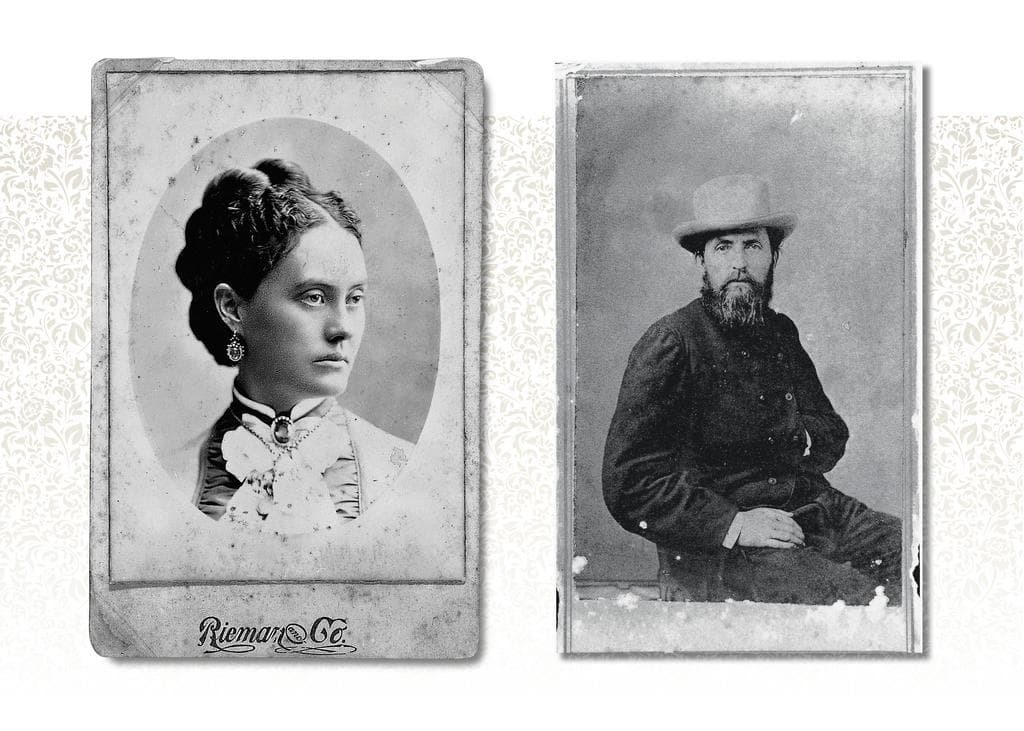

C.P. Ward was a native of Kentucky, arriving in Honolulu in 1853. Ward had a successful business where he operated a horse stable and hauled goods from Honolulu Harbor to other areas in Honolulu. Before marrying, he lived in Washington Place (where Hawaii’s Governors and their families currently live and what was once the private residence of Queen Lili‘uokalani).

Victoria Robinson Ward was born in Nuuanu to John James Robinson, an English shipwright and a large local employer, and Rebecca Kaikilani Previer, who was the daughter of a Hawaiian mother and French father. They were a prominent family in Honolulu society.

C.P. and Victoria married on Victoria’s 19th birthday in 1865. C.P. was nearly 20 years older than her. They made a home near Honolulu Harbor, where the present-day Davies Pacific Building stands. C.P. named the home Dixie, and in that home, they had seven daughters: Mary Elizabeth “Mellie,” Hattie Kulamanu, May Augusta, Annie, Lucy Kaiaka, Victoria Kathleen and Keakealani Perry.

After they were married, the couple amassed a large amount of land outside of the then-urban areas of Honolulu. They bought a parcel of land near present-day Thomas Square park, and in 1870, they bought an additional adjacent 12 acres in a public auction for $2,450. They added this land to pasture land that C.P had purchased near Washington Place and present-day Washington Intermediate School and some additional purchases to own 100 acres, which included the land where Ward Village now stands.

In 1880, C.P. and Victoria began building their home, hiring an architect named C.J. Wall who had also worked on the design of Iolani Palace. They would name the white, two-story house with white pillars and green shutters Old Plantation. The home stood where the Neal S. Blaisdell Center is currently located and the couple quickly began to develop the land to produce food, planting thousands of coconut trees and harvesting fish from the free-water-spring-fed fishpond.

On March 10, 1882, C.P. passed away from complications of a throat operation, leaving 35-year-old Victoria not only with seven young daughters but also a new house, a vast business and a large amount of real estate.

Despite her young age and husband’s death, Victoria proved to be a savvy businesswoman. Within a few years, Victoria would sell the businesses to her soon-to-be son-in-law, Frank Hustace, who had worked for C.P. And, she would lease out the salt operation near the Kakaako shore and parts of the family farm.

Victoria then turned her estate at Old Plantation, much of which extended to Ward Village today, into a working farm, selling salt, eggs, pigs, chicken, fish, firewood, ducks, taro, grass, bananas and coconuts.

Many of those coconut trees still stand in Honolulu today. And now, the historical plants are being reflecting in the landscaping of Ward Village today. Pua kenikeni, kou, milo, coconut, gardenia, Oahu sedge, kupukupu fern and rose jatropha are listed as plants that will be in Ward Village, according to a Hawaii Magazine story.

Also, a Ward Village post confirmed the biophilic design of Ward Village, saying, “Today, architects and designers are once again turning to plants and other natural elements to bring back the calm, serenity, and a direct connection to nature that was once found at places like Old Plantation.”

Furthermore, a Honolulu Magazine archive shares a descriptive story of the rich life at Old Plantation:

“In the latter decades of the monarchy ‘Old Plantation’ was a gay place. Liliuokalani, Emma and Kapiolani were frequent guests. Princess Kaiulani was a contemporary of young Kathleen Ward, and the two were close friends. There were lawn parties and balls, and much activity on the croquet and tennis courts. A rowboat provided pleasure on the tiny lake, long since filled in. ‘Old Plantation’s’ grounds then extended all the way to the waterfront, unbroken by Kapiolani Boulevard. There were more than two thousand coconut trees on the estate and a profusion of fruit trees and flowers, not to mention vegetable gardens and an area where turkeys, chickens, pigeons and pigs were raised to supply the family table. Many friends shared the bounty of this produce, and Hawaiians in need were never turned away empty-handed.”

As Honolulu embarked on the new century, the provisional government also embarked on new development, including roads and shoreline dredging projects, many which had major effects on what is seen today in Ward Village. After the overthrow of the monarchy with the ousting of Queen Lili‘oukalani in 1893, the Hawaii provisional government’s Board of Health declared the remaining Honolulu wetlands posed a health risk for mosquito breeding and other bacteria and needed to be drained.

Thus, much of Kakaako would be filled in. A seawall would be constructed, and Kewalo Basin would be 29 acres of new land in 1930. The shoreline road of Ala Moana Boulevard would become further inland due to construction. Ala Moana Beach Park was constructed in 1933 with infill from the dredging of the harbors and Ala Wai Canal. While the Kakaako land toward the ocean was “new,” a lot of it further from Waikiki was used to dispose of garbage from the growing Honolulu metropolis.

During this time, some working-class families also called Kakaako home, living in camps.

And what happened to the Ward’s 100 acres? Despite rapid development in Honolulu, it remained largely a part of the Ward ohana for many decades – with legal battles along the way. A 2019 Pacific Business News story by Janis Magin recapped the history:

“But as the city grew around them, there was more pressure to sell land. The family’s three-year fight against the City and County of Honolulu over the building of Kapiolani Boulevard landed Victoria Ward and her daughters in the newspapers many times from 1928 to 1931, often on the front page.

In late 1927, the city moved to condemn two parcels owned by Victoria Ward for construction of Kapiolani Boulevard — 15,560 square feet along the Ewa side of Ward Avenue, fronting what is today Symphony Honolulu, and 82,118 square feet on the Diamond Head side of Ward Avenue, along what is today the Blaisdell Center property.

By the summer of 1928, the city was in court arguing over the price of the two parcels — the city had offered $35,000, but Ward told the court the land was worth $146,000, according to a story in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin. A Circuit Court jury in November 1928 set the price at $38,714 (or $565,143 in today’s dollars).

In March 1929, she and her three unmarried daughters — Hattie, Lucy and Victoria Kathleen — sued the city to stop work on the road, but then lost their case in court. In late February 1931, the Territorial Supreme Court issued a final decision affirming the lower court rulings, according to a story in The Honolulu Star-Advertiser.

Two months before that decision, on Dec. 18, 1930, she formed Victoria Ward Ltd. with her three unmarried daughters and also her oldest, Mellie Ward Hustace…”

When Victoria Ward passed away on April 11, 1935, her will created a trust for her daughters Hattie, Lucy and Victora Kathleen to own the property while her youngest daughter, Lani, was allowed to occupy the home. Lani was the last daughter to die in 1961.

And Victoria Ward Ltd. would lead the way in developing the Ward’s remaining acreage.

In addition to the development of Kapiolani Boulevard through the Ward family property, the city of Honolulu also had their eyes set on another 23.6-acre portion of the Ward estate. This land was sold for $2 million in 1958 and now comprises the Neal S. Blaisdell Center, a multipurpose arena, exhibition hall, concert hall and more.

To the ocean side of Kapiolani Boulevard, Victoria Ward Ltd. still held the land, opening Ward Warehouse in 1975 and Ward Centre in 1982. Ward Warehouse, which once was home to a number of small businesses, such as restaurants, was closed in 2017 to make way for residential towers and Victoria Ward Park. Ward Centre is now known as Ward Entertainment Center (updated in 2002) with a deluxe movie theatre and Dave & Buster’s as well as other recreation and retail sites.

Then, in 2007, the next major phase of Ward Village began; Victoria Ward Ltd. sold 60 acres of land to General Growth Properties.

In 2008, General Growth Properties proposed the Ward Village Master Plan to the Hawaii Community Development Authority (HCDA), the state agency that was tasked by the Hawaii State Legislature to develop the Kakaako community in 1976. This plan was approved in 2009, and lays the foundation for the Ward Village that is unveiling today under Howard Huges, a spinoff from General Growth Properties.

Howard Hughes promises to preserve the legacy of Victoria Ward as they continue to develop the design-forward neighborhood. In the overview of the history on the Ward Village website, the company writes the following:

“Since 2010, our Hawaii-based team has been dedicated to preserving Victoria Ward’s legacy while moving forward on the master plan. By about one block per year, we’re transforming 60 acres of Honolulu’s ocean-front land into a design-forward neighborhood for all. While we’re building distinct high-rise residential towers using the world’s leading architects—which include market homes and reserved housing for Hawaiʻi residents—Ward Village is also offering a variety of community enhancements, including compelling retail, 2,500 free public parking stalls, public art displays, 116,000-square-feet of services, over 150,000-square-feet of parks, and more. As we make these improvements, we’re focusing on sustainability via smart growth, greener buildings and modern infrastructure. Through this residential and commercial development, we’re proudly supporting local job and business creation.”

Ward Village has hundreds of years of history that led to its transformation today. And, surely the next decades and centuries will be steeped in more history-making tales and transformations.

What is there to do in Ward Village? Explore all the options.

Learn about Ward Village's master plan and how it's changed.

Ward Village in Kakaako will eventually include 4,500 condos.

Newly built condos, microbreweries, hidden speakeasies, and more.

March's report features The Launiu Ward Village in Kakaako.

Launiu is a proposed mixed-use luxury tower with 486 condos.